The following recent headlines demonstrate how important that weekly paycheque is to workers and their families:

- 50 percent of minimum wage workers say they have to work more than one job to make ends meet

- Three quarters of all employees feel they live paycheck-to-paycheck to make ends meet at least sometimes; nearly a quarter feel they always do

- Almost half (48%) report it would be difficult to meet their financial obligations if their pay cheque was delayed by even a single week

- 46% [of working Australians] admit that they live ‘pay-cheque to pay-cheque’.

The financial impact of even a brief interruption in earnings due to a work-related injury or disease can be devastating. Despite the legislative intent of workers’ compensation laws, the simple reality is that many—perhaps the majority—of those who miss time from work due to a work-related temporary total disability never receive workers’ compensation for their lost wages.

Employers, family members, and even policy makers may assume workers’ compensation coverage is there for every case of work-related time-loss injury. The assumption may blind them to the serious gaps exist for many workers in the employed labour force. For some, understanding the gaps may provide the impetus to fill them. At a minimum, knowing that gaps in coverage exist will allow those with the resources to prepare for interruptions in earning due to workplace injury or occupational disease. Unfortunately, for many workers and their families, there are no resources to cover the gaps; using private savings or buying individual disability insurance coverage are not realistic options.

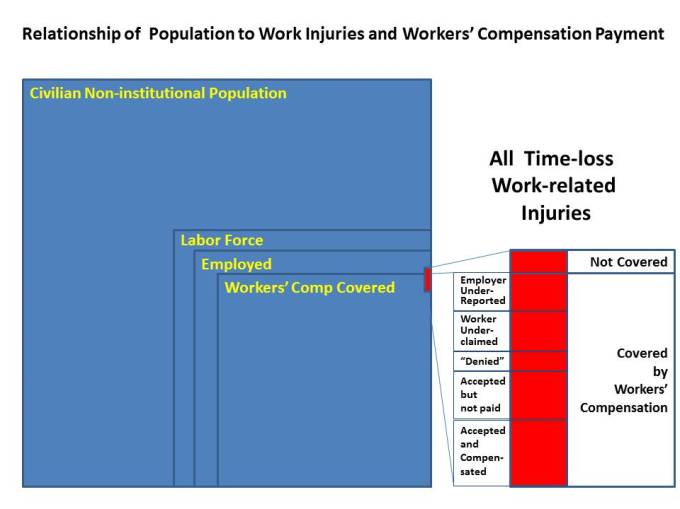

Work-related injuries can occur to anyone engaged in employment in the labour force. Clearly, those institutionalized or in the military are not available for employment in the broader labour force; those who are incapable of work, retired or otherwise withdrawn from the labour force are not available for work. Those who are unemployed but looking for work are available for work but any injuries that occur to them don’t arise from work so are excluded from this discussion. That leaves the subset of individuals engaged in work for themselves or someone else; it is from this population that work-related injuries occur; only a subset of those are covered by workers’ compensation.

As may be noted in the figure below, work-related injuries that result in time away from work can arise from employment within the scope of workers’ compensation or outside it (self-employed, exclude small enterprises, and excluded occupations or sectors). Inclusion within the scope of workers’ compensation coverage, however, does not automatically lead to compensation.

- Injuries to workers outside of workers’ compensation coverage are excluded

First, let’s look at the intentional exclusions from workers’ compensation coverage. The actual coverage of the employed labour force ranges widely by jurisdiction. Many states and provinces define the industries and sectors that must carry workers’ compensation coverage; a few mandate blanket inclusion then identify specific exclusions. Common exclusions include agricultural workers, domestics, professional sports players and self-employed. In some jurisdictions, firms with fewer than four or five employers may also be excluded from mandatory workers’ compensation coverage.

NASI estimates workers’ compensation coverage in the “total workforce” is estimated by to be approximately 90% in the US [2013 data]; AWCBC puts the Canadian “employed labour force” coverage rate at about 84% [2013 weighted average] but the calculation method is somewhat different. Australia reports that 92% of its employed labour force is covered by workers’ compensation (often called “WorkCover”).

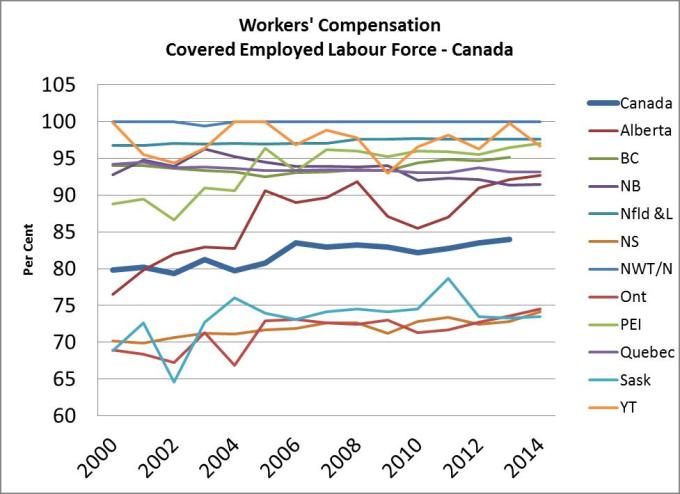

In Canada, there is a standardized calculation methodology that allows province-to-province comparisons (including self-insured and federal employees in the covered percentage). The recent calculated “percentage coverage” rates for each province/territory and the Canadian average are shown in the following figure:

While the average is approaching 85% and has been rising since 2000, there is a clear divide above and below the national average.

As far as I can tell, there is no similar analysis on a state-by-state basis in the US. It is reasonable to assume, however, that there are states where more than 95% of the employed labour force is covered and others where the percentage may be as low as 75%.

“Self-insured” employers are typically included in the calculations as long as they are required to provide legislatively mandated workers’ compensation coverage. Firms outside the scope of coverage or not required to comply with workers’ compensation law are typically excluded from calculations. As a matter of practice, such firms may well purchase and offer disability insurance, although a few will carry the risk and manage their own liabilities.

As an aside, there are two main types of self-insured employers:

- those that are self-insured and self-administer their own claims (or contract a third party administrator to do so on their behalf), and

- those who are self-insured without self-administration.

In most Canadian provinces, self-insurance does not include self-administration. Self-insured employers are financially responsible for their own claims but the administration of the claim including initial adjudication is administered by the provincial exclusive workers’ compensation system.

Australian workers’ compensation coverage alone would be around 80% of the employed labour force; adding the “self-insured” employers, the figure rises to about 90% [based on 2013 data]. It should be noted that self-insured in Australia means self-insured with self-administration (including third party administration) in conformity with benefit levels mandated by the workers’ compensation legislation. Self-insured firms in Australia manage their own financial liabilities arising from their own claims.

The implication here is that intentional exclusions in Canada, the US and Australia result in 10% to 15% (on average) of employed members of the labor force outside of the scope of workers’ compensation coverage. If the rate of injury to this excluded group is similar to the rate experienced by those within the scope of coverage, then 10% of 15% of time-loss or wage-loss resulting from workplace injuries are excluded from the possibility of compensation.

As may be noted from the Canadian data, variation in percentage covered in some jurisdictions over time. This is rarely due to sudden changes in the scope of coverage. More often than not, the variation relates to changes in the distribution of the employed labour force among sectors of the economy (including sectors excluded from mandatory inclusion in the workers’ compensation system).

The “scope of coverage” decision is a public policy choice but it has important consequence for those outside the coverage umbrella. Clarity around who is excluded and why is important and necessary in order for workers to assess their own financial risk. Those who can afford it may choose to purchase private disability plans.

Intentional exclusions explain why one segment of work-related time-loss injuries that are not compensated. Being within the scope of workers’ compensation coverage, however, does not automatically result in payment of compensation for days lost due to a work-related injury and disability.

- Injuries Accepted and Compensated

This is the firmest statistic you can find at a state or provincial level. It is typically reported on the basis of a claim where “indemnity” or “wage-loss” compensation was paid for “temporary disability”. Some jurisdictions make a distinction between temporary total and temporary partial disability payments.

For the purposes of this analysis, any workers’ compensation claim that has even a partial day of wage-loss compensation paid would be considered in the count. Medical-aid claims (or “healthcare only” claims) are not considered as “accepted and compensated” for the purposes of this analysis.

Time-loss claims that are “accepted but not paid” are discussed later but introduced here to contrast with the compensated case. A worker who experiences a Monday injury (in a typical Monday to Friday work week) and is away from work the next three days (Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday), then returns to work Friday may receive no wage-loss compensation if the jurisdiction has a three-day waiting period; doctor bills and medication may be paid but no compensation for time away from work would be payable because of the three day waiting period. Such a claim would be counted as accepted but not paid.

In some provinces, employers may pay the first week or two of wage loss in order to maintain income continuity for injured workers. The employer is re-imbursed by the workers’ compensation insurer thus maintaining the tax-free status of the compensation. In Australia, employers may be required to pay wage loss compensation for the first 5 or 10 working days before workers’ compensation payments for wage loss begin. This sort of “employer deductible” would be counted as an accepted claim with compensation paid.

The statistic for “work-related time-loss injuries with temporary disability compensation” may be reported as or along with an “injury rate”. This may be misleading depending on the denominator used. As indicated in the figure and explanation above, this fraction of work-related injuries relates only to covered employment and only to claims that received payment. Unless coverage is near 100% and wage-loss compensation is paid for all time away from work (that is, no waiting period), this is more aptly entitled “paid claim for covered injuries rate”.

These first two categories – workers’ compensation “excluded” and “accepted and compensated” might be assumed to tell the whole story but research evidence suggests otherwise. Some studies of fatalities and cases involving hospitalization show medium to high correlation between hospitalization records and workers’ compensation [for example, see

Koehoorn M, Tamburic L, Xu F, Alamgir H, Demers PA, McLeod CB, “Characteristics of work-related fatal and hospitalised injuries not captured in workers’ compensation data”, Occup Environ Med doi:10.1136/oemed-2014-102543]; however, most research studies reveal large discrepancies between cases reflected in workers’ compensation data and other sources such as hospital records [see Boden LI, Ozonoff AL . Capture-recapture estimates of nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses.

Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:500–6.

doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.11.003].

Next we examine four main categories of work injuries that are not compensated.

- Time-loss Work-injuries Accepted but Not Paid

Workers with otherwise acceptable work-related time-loss injuries may be “disentitled” from receiving compensation.

- Waiting period non-payment

As noted above, waiting periods can result in non-compensation for wages lost due to absences caused by work-related injuries for cases within the scope of employment. Waiting periods are “worker deductibles” and have been eliminated from all but two Canadian jurisdictions and all Australian jurisdictions. In the US, waiting periods range from three to seven days. Most states have a “retroactive period” that waives the waiting period for work absences that extend beyond a given duration (two to four weeks, typically). Time-loss claims with no wage-loss compensation are considered “accepted but not paid” for this discussion.

- Concurrent employment or other earnings disentitlement

Otherwise acceptable claims may also fail to qualify for compensation. In the case of concurrent employment, for example, an injured worker may be disabled from one job but able to work in a second, concurrent job. Wages from a second or other multiple employment(s) may negate any earnings loss from the injury employment. Such a claim would be counted as accepted but not paid.

- Process issues resulting in non-payment

Still other claims are accepted but no payment is made to the worker because of lack of contact with the worker. The transient or tenuous nature of the injury employment may be one reason for this phenomenon. For example, a migrant farm worker may suffer an injury, get immediate treatment then return to his or her home country to convalesce. Assuming farm work and migrant agricultural workers are covered and the injury properly reported, the immediate medical bills may be paid (often directly to the physician, hospital or other provider) but any payment to the worker may be impossible due to lack of contact information. Such a claim would be counted as accepted but not paid.

As noted at the beginning of this article, many workers have little or no financial reserves. The lack of financial resilience means all aspects of their lives are put in jeopardy as the result of even a short work absence due to work-related injury. Workers move to lower-priced accommodation, live with relatives in an unknown address in or out of state (in the case of temporary foreign workers this may be out of country) to have assistance and support in recovery, leave the city to reduce costs, etc. Such cases may still have “technical entitlement” to wage-loss compensation but the insurer may “suspend payment” the claim processing due to lack of contact with the injured worker. Medical bills and hospital bills might be paid if they were directly submitted to the insurer.

- “Denied” (or “not decided”) claims

Employers may properly report injuries and workers may fill out all the appropriate claim forms for injuries they and even their physicians believe arose in the course of and out of the duties associated with their work but the claim may be “denied”. This term may or may not have a specific meaning for a particular jurisdiction. If an injured employee applies for benefits but his employer is not properly insured, the claim could be denied or “rejected”. Many jurisdictions have laws that will allow coverage of injuries where the employer should have been registered or insured but this is not universally true.

A more common category of denied claims involves those where the insurer accepts that the employer is covered and that the employee is a worker but does not accept that the particular injury occurred as a result of work or that the consequences of the injury are sufficient to warrant time away from work. Back pain may have a sudden onset at or after work but linking work to the injury may be complicated and contestable. Stress, repetitive strain, and cumulative damage from repeated incidents are frequently contested by the insurer. In these cases, the worker and even the employer may well believe in the “work-relatedness” of the injury but the insurer may rule the injury did not arise from work.

Statistics on denied claims (which may be reported as “rejected”, “disqualified”, or “disallowed”) are rarely reported. When they are, it is difficult to assess what portion of the claims could be considered work related. Few claims that are initially denied are subsequently appealed or reviewed for the accuracy of the denial decision. To workers and many others, these claims are often the genesis of mistrust of the system. That said, workers’ compensation has a limited mandate and the work-relatedness or causation decision is critical to the integrity of the system.

Workers may “over-report” injuries (including those adequately treated with on-site first aid; disinfect and bandage an abrasion, for example) to record an exposure, build evidence of poor or unsafe working conditions, or because of misinformation on the nature of workers’ compensation. These cases are often turned down for any compensation.

Some quite serious injuries that occur at work may be denied because of “horseplay” or other actions that essentially take the worker out of the course of employment.

An injury may well arise from work activities and be documented by both the worker and the employer as being work related; the insurer may also agree and accept the claim to pay doctor bills and medication but rule that wage-loss compensation is unwarranted. Despite a valid work-injury claims, no compensation is payable because the worker is deemed able to work (not totally disabled).

Despite the potential negative connotation of the terms “rejected, disallowed, disentitled, and denied”, these decisions are essential components of adjudication in workers’ compensation. Legislation and policy define the limits of the coverage; acceptance of cases beyond that scope undermines the will of the legislature and the financial integrity of the system. The consequences of not properly adjudicating claims include losses due to fraud and abuse that would increase costs for employers and threaten benefits for legitimate claims.

An injury that is attributable to work may carry secondary benefits that motivate the filing of a claim that will or should be ultimately and properly denied. In the US, the lack of universal health care may be a motivator to opt for an attribution to work of an injury of uncertain origin. In the absence of a clear etiology, the attribution of a back injury to work activity, for example, may afford access to medical care and even improved social status or family support.

Few jurisdictions release any information on denial rates of initial claims. Even where data are available, it is hard to tell how many denied claims might eventually have involved wage-loss compensation.

There is also little data on claims that have incomplete information required to make a decision. Similar to claims that are decided but payment suspended due to lack of contact with the injured worker, those with work-related time-loss injuries who move, return to their home country, or otherwise lose touch with the insurer may lose possible entitlement because of the lack of continuing contact or supply of additional information needed to complete the claim process. In some states, there are legislated timelines for deciding claims. Claims that are otherwise acceptable may be denied in order to meet time limits imposed by the regulator. Provisions for reconsideration or “unsuspending” claims may exist but data are hard to come by.

- Worker under-reporting (including non-reporting)

Assuming an employee works within covered employment and suffers a time-loss injury, there are several reasons why the injury might never be reported to the workers’ compensation insurer even if the employer is otherwise supportive of workers’ compensation reporting and claiming.

- Third-party action (considered, initiated or in process)

Injured employees are not permitted to sue their employers or other workers for work-related injuries that arise in the course of their employment. This “statute bar” is an essential component of the workers’ compensation “exclusive remedy” that is at the core of the grand bargain or historic compromise that is workers’ compensation. Where a third party is involved, and that third party is not an employer or worker under the workers’ compensation legislation, the worker may have an option of pursuing an action. The choice to pursue such action may prevent a workers’ compensation claim. In some cases, a worker may claim workers’ compensation benefits and subrogate the right of action against the third party to the workers’ compensation insurer. This, however, removes the decision-making from the injured worker.

- Gradual-onset and Out-of-time

Work injuries and occupational disease may not become apparent immediately. Most jurisdictions have time limits within which a work injury or occupational disease must be reported or workers’ compensation claimed. With few exceptions, former workers—those no longer in the workforce or those who are unemployed at the time of a claim—are unlikely to have a successful workers’ compensation claim. Exceptions may be made for cases where the diagnosis was delayed or other barrier prohibited the timely report and claim.

The connection between work and the development of disease or an injury may not be immediately obvious. Unlike injuries that have a single, sudden traumatic origin, some mental injuries such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) may develop over time with disability occurring as a result of one or several events that happened over time. First responders, for example, may be exposed to horrific scenes of death and violence. The psychological toll may result in non-disabling or disabling conditions (including sleeplessness, depression, anxiety, anger) but may also result in more serious issues not immediately proximal to a specific definable event.

Bullying in the work environment (from customers, bosses, or co-workers) is a recognized workplace health and safety issue. By definition, bullying or harassment (including sexual harassment) is a pattern of behaviour, not a single event. Some jurisdictions have specific occupational health and safety regulations or standards that require employers to act to prevent bullying or harassment; workers’ compensation systems may cover injury as a result of bullying or harassment but the lack of consistency may contribute to under-reporting. Workers who suffer illness or injury as a result of bullying in the workplace may be unaware of compensability. Worse yet, workers may fear further bullying or harassment if a claim is made or the pattern of incidents is reported.

Why wouldn’t a worker claim workers’ compensation for a work-related time-loss injury? Leaving aside employer inducements and active claim suppression (which we will get to shortly), there are several reasons including:

- Lack of knowledge of rights

- Misconceptions about benefits

- Substitution of other income supplement

- Barriers of language, culture

- Fear of collateral consequences (undocumented worker fearing detection and deportation)

- The “hassle” factor (forms completion, retelling injury story, meetings)

- Social or work-group pressure

This last item can be quite significant. In my career as a vocational rehabilitation consultant I never saw a roofer or faller with a minor injury. Unless they were taken from the worksite on a stretcher, workers in these occupations seemed to view a workers’ compensation claim as a sign of weakness. Even among nurses and caregivers, there was a sense that some injuries are “just part of the job”. The social stigma in these occupations may be changing but is still present but no one should have to accept work injury as a consequence of work.

As noted earlier, many workers have little or no financial reserves. For these individuals, the financial impact of a waiting period that may be as long as a week coupled with the delay between date of injury and first payment can be an overwhelming concern. For workers that have access to paid sick leave, the decision to opt to use paid sick leave that ensures no loss of earnings and no delay in payment over workers’ compensation is an obvious choice. Unfortunately, this externalizes costs to others. Sick leave is a taxable benefit often factored into the wage cost in collective agreements. Using sick leave for work injuries removes the focused financial incentive workers’ compensation provides in promoting workplace health and safety.

The hassle factor refers to the effort cost of filing a claim relative to the expected benefit. If I think I will get little or no benefit from making a claim, why should I bother? A few jurisdictions have “dial a claim” services or establish a claim on the basis of any report of injury from a physician, employer or worker. Some jurisdictions require claims to be submitted in specific manual forms through specific channels with the employer. The hassle factor of the latter may make filing for short time-loss not worth it to the individual.

Under-reporting by workers not only deprives the worker of entitlements or externalizes costs to others, it dampens an important safety feedback loop and distorts the risk profile of the workplace. Those distortions may result in underestimation of hazards and risks creating an information vacuum or asymmetry to the potential detriment of workers and others in the workplace.

- Injuries under-reported by employers

Under-reporting by employers have similar consequences to under-reporting by workers but the underlying consequences and motivations are different. The categories here include the following:

- Benign Non-reporting or Misreporting (no active intent)

Benign “non-reporting” is not direct claim suppression but may relate to a misunderstanding of requirements or administrative barriers related to poor training or administrative systems. Training deficits and lack of experience are often at the route of the issue. Employers, particularly smaller ones, may rationally and properly focused on production issues and the challenges related to meeting staffing demands that arise following an injury; reporting may not be seen as a priority particularly if the procedures are not well known or systems lacking.

- Intentional Under-reporting (active intent)

...Experience rating causes the under-reporting to a WCB of occupational disabilities, it creates false statistics that tend to diminish OH&S… Experience rating also creates an incentive for employers not to report to a WCB disabilities sustained by a worker that employers have a statutory duty to report.” [Terence Ison, “Reflections on Workers' Compensation and Occupational Health & Safety" (2013) 26 C.J.A.L.P. 1-22] .

In some jurisdictions, it is the responsibility of the employer to report the workplace injury to the workers’ compensation insurer or authority. This requirement is over and above requirements by the occupational health and safety authority unless, of course, the insurer and the OH&S agency are one in the same (WorkSafeBC, for example).

To encourage reporting, legislators often set time deadlines and impose penalties for non-reporting or delayed reporting. However, there is no centralized source of information on the prevalence of non-reporting or delayed reporting by employers.

- Employer claim suppression (intentional indirect or passive)

Whereas benign and intentional under-reporting relate to direct action (or inaction) by employers, subtle and overt claim suppression by employers induce actions (or inactions) of workers with regard to claiming workers’ compensation for time-loss injuries. One study summarized the issue this way:

Employer inducement can be either overt or subtle. Overt inducement consists of threats and sanctions. Subtle inducement can take four forms:

(1) appeals to loyalty,

(2) willingness to pay wages and medical benefits in lieu of a workers’ compensation claim,

(3) group-based incentive programs that foster peer pressure to suppress reports of injuries, and

(4) perceptions that an injury will diminish prospects for promotion or increase the risk of lay-off. [Prism Economics and Analysis, 2013].

These inducements are more difficult for regulators to detect. They are most effective on employees who are most vulnerable. These include workers with limited knowledge of their rights, few alternative employment prospects, and precarious employment situations. That said, large firms as well as small have been found to engage in these activities.

The likely fraction of work-related time-loss claims that receive compensation is a function of these factors. Studies in the US and Canada along with published statistics can help fill in the values for a given jurisdiction.

This is critical information for policy makers as well as workers and employers. If the fraction of accepted and compensated work-related time-loss injuries is unacceptably low in a given jurisdiction, then administrative and policy actions can be taken to improve the percentage. Actions include:

- Expanding the scope of coverage to include currently excluded occupations and sectors

- Promoting coverage to those with option of coverage

- Educating workers and employers on their rights and obligations

- Streamlining application and benefit payment systems

- Specific programs for those in precarious and contingent employment

- Identifying administrative and policy barriers that result in denied claims